Allen County residents dial 911 about 3,500 times a month. But a few of those calls put a questionable burden on local emergency services.

In a typical week, 911 emergency units are called to help rouse children out of bed before school, stop brothers and sisters from fighting and keep estranged couples from abusing each other and each other’s property.

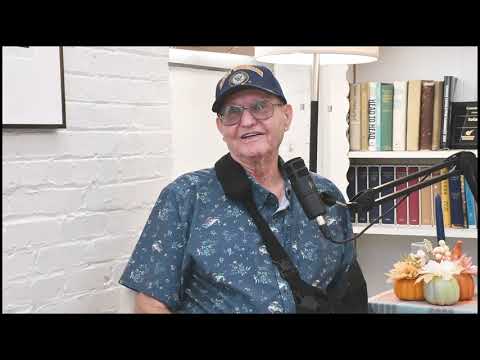

“Is that the best use of our law enforcement resources?” asked Wade Bowie, Allen County district attorney. “No, but it’s a balancing act.”

Fielding nearly 7,600 emergency calls since Jan. 1, the Allen County dispatch center does not separate legitimate calls from those most reasonable people wouldn’t make, nor does it have the capacity to. Rather, each call is relayed to the Iola, Humboldt or Moran police departments or Allen County sheriff’s officers where a decision on a request’s priority is made.

“I don’t want to discourage people from calling (911) because what might seem like a (minor) call can sometimes escalate,” said Angela Murphy, Allen County dispatch center director. As an example, Murphy told of a mother this week not being able to get her son out of bed. “In the long run that could have easily turned into a family dispute.”

Depending on the volume of calls coming into the dispatch center and the number of law enforcement officers on patrol, individual officers rate each call’s level of need and then respond accordingly.

No matter how trivial a call might seem, the Iola Police Department is happy to provide any service to the public,

granted officers aren’t occupied with more pressing matters, said Jared Warner, Iola Police Chief.

“We take all calls that come in because at that point, someone feels they can’t handle a situation and needs police intervention,” he said. “What is heard on the radio might not be the case when officers show up.”

Often, the person calling the 911 dispatch center reveals only a fraction of the information needed to truly assess a situation, whether it be criminal or civil, Warner said.

“We’ll get there and it can end up being something totally different or more significant than what was originally called in,” he said.

Tending to a seemingly minor call like a noise complaint or a parent in need of assistance doesn’t burn up additional resources for a law enforcement agency, Warner said, because responding officers are already on duty.

An officer’s response to such situations also can save government resources. Citing a parent’s request for assistance from the law to get a stubborn teenager out of bed in time for school, Bowie said having officer assistance can save a family a lot of trouble down the line.

“Parents worry about truancy. I’ve got six truancies cases I’m going to be filing today,” Bowie said pointing to pile of papers on his desk.

Each school has a designated truancy reporter that notifies social services or the county attorney’s office if a child misses more than seven school days within an academic school year without parental permission.

“And technically the parents are responsible up until the child turns 18,” Bowie said.

Bowie said many times parents are “at their wit’s end” with a child’s behavior, stubbornness and general resistance and simply don’t know what option they have left.