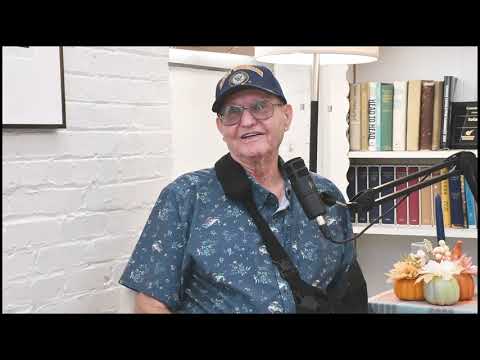

CHANUTE — Tri-Valley Developmental Services has for years endured the type of state funding cuts now being levied on a number of Kansas agencies, but these cuts, claims Tri-Valley’s executive director Tim Cunningham, were just a warm-up. FAST-TALKING, articulate, with a streak of eager pugilism, Cunningham is probably a guy you’d rather be fighting alongside than against. It’s not that he’s unfriendly. He’s very friendly. He has a “Volunteer of the Year” plaque on his office wall in Chanute, and he keeps a book about Dachshunds on his shelf. CUNNINGHAM believes the state’s approach to Tri-Valley is one of deliberate fiscal starvation. “Their goal is to screw it up so badly that there’s no going back…. Brownback’s belief is that people should rely upon their families and churches, and that the state government should get out of this. The problem is the state constitution requires the state to take care of people with disabilities.”

“Next year is when they’re really going to start hammering us.”

Through a combination of partisan social policy and “complete bureaucratic incompetence” the state, according to Cunningham, has reduced his agency’s operations “to a bare bones level — and [Brownback’s] not done axing.”

The three-part mechanism by which Tri-Valley was funded for much of its early history — state grant funds, state aid, and home and community-based service (HCBS) Medicaid — has altered considerably since Cunningham assumed his role as the head of the non-profit nearly eight years ago.

The grant program has been eliminated; state aid has fallen annually — Tri-Valley, which provides residential- and employment-based services to developmentally disabled adults, currently receives $102,985, down from approximately $120,000 two years ago; and the Community Developmental Disability Organization (CDDO) budget has gone from $220,118 in 2007 to $163,371 last year.

But it is the impending changes to the criteria by which clients of Tri-Valley are judged eligible for subsidized services that has Cunningham grinding his molars of late. “They’re changing our assessments to make it a lot more stringent, to where, before, someone who may have been getting a lot of services is now getting very little…. And so even though it’s not a cut up front, they’re going to cut our funding by changing the assessments. It’s a way for them to save money.

“And do you know who’s reaping the money?” asked Cunningham. “The managed care companies.”

In 2013, Kansas, under the Medicaid program KanCare, became the first state to refer decisions about the eligibility and care of its developmentally disabled population to national for-profit insurance companies and away from local non-profits and county-based agencies.

Currently, these managed care companies are losing money, said Cunningham — “their goal is to make money, so they’re going to cut wherever they can to get that profit back.”

The cumulative effect of the cuts has meant that Tri-Valley has had to reduce its staff over time, from 172 employees when Cunningham took over to “about 142” today. Because of short-staffing, said Cunningham, Tri-Valley’s clients “are not getting the care or the training or the education they need.

“I’ve been in this field 24 years now and the last four years have done more damage than that whole time combined…. They’ve cut our funding back so much that we can’t get people out there to get employed. [The state] wants us to reduce reliance upon government but how can we do that when we can’t get people out there to get the jobs they need so they can get off that reliance.”

But he is ferocious in his defense of those developmentally disabled individuals in Allen, Neosho, Woodson and Bourbon counties who come under Tri-Valley’s care and who, he believes, are being systematically underserved by a state whose own constitution mandates that it meet certain standards of sufficient care.

In a time when politicians and executives hide their true opinions behind a blanket of polite cliché, Cunningham is refreshingly blunt.

“It’s complete incompetence up there. We’ve got kooky legislators in Topeka, and the problem is they keep getting reelected.

“I feel like we’ve taken our car in to get an oil change and they’ve gone and completely gutted the engine, flipped it upside down, then sideways, and now they expect it to run.”

Cunningham is a lifelong Republican, a self-styled moderate, and someone who — prior to becoming one of the governor’s most vocal critics — cast his vote for Sam Brownback in the 2010 election.

But his dismay at watching the forced erosion of his agency has pressed him into a role he hadn’t anticipated. “I spend all of my time advocating for us now, with state legislators and the media, wherever I can. Before, my job was more hands on.”

Last month Cunningham convened a meeting that included a couple of state senators as well as representatives from the Kansas Department for Aging and Disability Service (KDADS).

The meeting was a chance for Cunningham to touch on the second pillar of his grievance against the state, which, after funding, concerns what is, in his view, this administration’s chronic mismanagement.

In preparation for the meeting Cunningham organized a document listing more than 100 “issues with managed care and KDADS,” which cataloged the ongoing failures in communication, lapses in contract obligations, electronic filing inconsistencies, and rampant billing errors, which every month force Tri-Valley to expend undue effort trying to obtain proper reimbursement from the managed care companies.

Cunningham has received a partial — if largely unsatisfactory — response to his list of issues from a representative of KDADS, who has promised him a fuller accounting in the coming days.

Cunningham is aware that his tones are occasionally strident. “If I wasn’t this vocal, they’d run all over us. I think our only saving grace is that we’re one of the only ones in the state who has been vocal about KanCare. Our system is the only one that fought back, and we’re still fighting.”

It also may have something to do with the fact that alone among social service agencies, groups like Tri-Valley care for individuals — men and women with cerebral palsy, Down syndrome, severe autism, and profound intellectual disabilities — whose conditions render them largely voiceless, or at least lacking the kind of voice that can get the attention of the statehouse.

“[This administration] seems not to understand,” said Cunningham. “We’re not talking about people who get cured and make progress. You know, our clients may make incremental progress, but they’re not cured — they’ll never be cured. And do you know what? It is the state’s responsibility to take care of them and the state doesn’t want to do it.

“The reason we complain is that we don’t want them to cut us. And when we complain loud enough, they back off. Or at least they did. Now they don’t even listen — they cut.”