Editor’s note: At this point, there is sufficient evidence to doubt the veracity of nearly all the claims of this article’s subject. We have since published an update to this story. You can read it here.

The plan was to interview a young man whod recently been run over by a bale of hay.

This man had been standing near the hay trailer, helping unload the cylinders, when one of the giant, 2,000-pound bales slipped from the tractors front spikes and began rolling his way. The tractor operator honked his horn in warning. The young man heard it and turned around, his feet sliding in the loose gravel but it was too late. The bale knocked him down and rolled completely over his upper half. He remained on the ground for a couple of minutes, trying to catch his breath. The accident had knocked the wind out of him. The tractor operator, who happened to be the mans younger brother, came to check on the man. Hey, the younger brother said, youre not supposed to be sleeping on the job. The man got up, dusted himself off, said a few bad words, and went back to work. The next day it hurt to breathe.

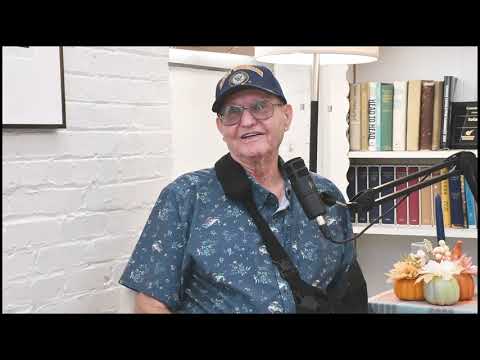

It took the man a week to go see a doctor. Eventually, I thought maybe I had pneumonia, said the man. I had a collapsed lung before, when I was in the service, when I got shot, and thats what it felt like. So that was my initial reasoning for going in. The doctor examined the man, did some X-rays. The result: fractured ribs, a bruised lung lining, some damage to his neck and to the tendons and ligaments in his left shoulder. He was given a breathing machine to take home a small device that gauges the strength of his lungs and warned never to let something the size of a small car roll over him ever again.

And that is the story of Brandon Griffith, the man who was flattened by a hay bale.

FARMING: A NOBLE BUT HAZARDOUS JOB this was to be the thrust of the story. I would call around, check in with area farmers, record their tales of ag-related injuries. A sleeve caught in the header of a combine. A tumble into the grain bin. I would combine their stories with Griffiths, stir in some statistics alternating human detail with hard data; the usual newspaper shtick and then conclude that farming is, well, a noble but, yes, also hazardous job. A competent piece of service journalism.

But then sitting with the man in his girlfriends Burlington trailer as a nine-week-old kitten pawed at Griffiths tattooed arm, I remembered something hed said 30 minutes earlier. Wait, I asked, dependably slow on the uptake, you were shot?

And so this is the other story of Brandon Griffith.

TWO YEARS ago which was about five years after most Americans had stopped paying attention to the war its sons and daughters were fighting in Afghanistan Brandon Griffith and his unit were called out to investigate an explosive device on a road north of Kabul. Griffith, a bomb technician, was one of two officers in the convoy that day. A convoy always travels with two officers: in the event that one is killed or injured, the other is on hand to give orders. The 37-year-old Burlington native had at that point been in the Navy for 18 years. He was old guard. Hed worked his way up from E1, the lowest rank in the military, to E9, and then, finally, to chief warrant officer.

The mission road that September day was long. The convoy was driving directly into a blinding sun, which stared down on the Americans from above a nearby hill. Griffith held on to Phoenix, his bomb dog, a Rottweiler-Lab mix hed nursed from the time the dog was a pup. All was still in the Humvee. It was the silence of the just-before.

Suddenly, as all these moments must feel when a loud tear rips through the fabric around you, the lead vehicle was hit by a rocket-propelled grenade. The Americans shifted into gear. Orders were given for the soldiers to dismount and return fire.

Griffith, with Phoenix by his side, readied his weapon and exited the vehicle. But just as he rounded the hood of the Humvee, he was hit in the back by sniper fire. His vest stopped the bullet from entering his body but the force was enough to spin him around, at which point whoever had Griffith in his crosshairs fired again and the officer was shot through his front. This time the bullet, which grazed the bottom of his vest, entered his right side, just above the waist, slicing through his intestines and lodging deep in his guts. Clipping the vest had the effect of shattering the copper around the bullet, turning one deadly projectile into nine or 10, and scattering shrapnel into his liver, his bladder, his pancreas, and the surrounding tissue.

Griffith lay in the dirt. Blood coursed from the hole in his side. Gunfire continued to pelt the area, coming from somewhere in the hills. Phoenix ran to Griffith and, gripping one side of the soldiers vest in his jaws just as hed been trained to do he pulled the officer behind a wall and out of the rain of gunfire. The dog remained at Griffiths side until the corpsman arrived.

Im laying there thinking, This is how Im going to die, and my dog is looking at me like What do I do? What do I do? What do I do? Griffith recalled. And thats the thing I was more worried about; not that I was going to die, but that my dog looked scared. Oh, my dog is scared, I cant die right now, I cant go. I cant go. I was like, Man, please dont let my dog see me die like this. Thats my buddy.

WHEN THE corpsman made it to Griffith, the unit was still catching Taliban fire. The lead Humvee was in flames, the three U.S. soldiers inside were dead, either killed in the explosion or burnt in the minutes after. The corpsman pumped the injured CWO full of morphine. At the time, no one knew Griffith was allergic to the drug. The morphine sent Griffith into anaphylactic shock and the medic had to insert a tube down his throat to keep his windpipe from closing.

Once the gunfire had subsided, Griffith was rushed back to the forward operating base, where he was loaded onto an airplane and flown to Germany for emergency surgery. Because Griffith had a collapsed lung, which is vulnerable to the excessive pressure of high altitudes, the plane, which was not combat-equipped, had to fly below 10,000 feet. Although it received an armed escort out of Afghanistan, the aircraft remained in plain view of the enemy and within reach of its weapons the entire time.